Whitney Plantation – The First Museum Dedicated to Slavery

Whitney Plantation is a former plantation site in Louisiana that has a distinguished history of slavery. In the past, a generation of Africans and their descendants were enslaved here to grow indigo, rice, and sugar. On December 7, 2014, Whitney Plantation opened to the public as a museum. Today, visitors come here to learn about the South’s turbulent past. It exposes the dark history of enslaved people and addresses the crimes against humanity head-on without sugar-coating any of the facts.

Visitors worldwide come to Whitney Plantation for the accurate history of slavery, to pay homage to those who lost their lives, and to see firsthand what plantation life was like. If you are visiting the South, this is the one plantation you should tour.

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure and privacy policy for more information.

About Whitney Plantation

A short drive from New Orleans takes you to Whitney Plantation in Wallace, Louisiana. Founded before the Civil War, it is the first slavery museum in the United States. In the 1750s, German immigrant Ambroise Haydel bought this land in Louisiana and named it Habitation Haydel. The place has a long history of slavery culture.

This plantation is exclusively dedicated to educating people about slavery. The Whitney Plantation Historic District is on the National Register of Historic Places.

If you take the tour here, you will see the world through the eyes of the enslaved people who lived and worked on an eighteenth- and nineteenth-century indigo and sugar plantation. This plantation does not glamorize, endorse or celebrate plantation life. It condemns it yet provides a historically accurate account of life on a plantation.

Whitney Plantation Through the Ages

Ambroise Heidel, a German immigrant who earned great wealth cultivating indigo, acquired the Whitney Plantation in 1752. The plantation was transformed into a sugar production operation by Heidel’s youngest son, Jean Jacques Haydel, Sr. A single grinding season produced 407,000 pounds of sugar. Like on any plantation at the time, enslaved black people were the primary source of labor here. More than 350 enslaved Africans worked on the plantation. The enslaved people at Whitney Plantation were continuously beaten, malnourished, and overworked. This harsh environment caused enslaved people to die.

In 1867, Brandish Johnson of New York purchased the plantation from the Haydel family, renaming it after his grandson, Harry Whitney. Between 1880 and 1946, Pierre Edouard St. Martin, Théophile Perret, and subsequent generations of their families owned the plantation. In 1990, Formosa Chemicals and Fiber Corporation acquired it from Alfred Mason Barnes of New Orleans.

Formosa Chemicals and Fiber Corporation intended to operate a chemical-based manufacturing facility. However, the community turned down yet another chemical plant in an area already known as “cancer alley.”

Whitney Plantation Museum

Throughout history, ownership of the plantation has shifted many times. Many buyers wanted to use the plantation for business purposes. The plantation’s use would not change dramatically until the late 1990s.

New Orleans-based attorney John Cummings purchased the 1,700-acre site in 1999 to restore it as a museum to tell the story of slavery. He spent $8 million of his fortune on research, restoration, and artifacts. Cummings was interested in telling the tale of slavery because no one else was, so he decided to do it himself.

The idea was developed 13 years ago by Senegalese scholar Ibrahima Seck. Seck inspired Cummings to turn the Whitney into a slavery museum. Cummings’ goal was to cut ties with all that is evil and begin righting some of history’s crimes with the museum. Many visitors feel the museum is a first step towards accepting the region’s troubled past.

Whitney Plantation opened to the public as a museum on December 7, 2014

Mr. Cummings owned and operated the property for 20 years, from 1999 – 2019. In 2019, John Cummings donated the museum, which is now a 501(c)(3) governed by a board of directors.

Note: The United States is home to more than 35,000 museums that ensure our nation’s culture and history are memorialized – Whitney Plantation is the first dedicated to slavery. However, many have challenged this claim citing museums such as The Lest We Forget Museum of Slavery in Philadelphia and Cincinnati’s National Underground Railroad Freedom Center.

I’ve never been to either so I can’t offer an opinion here. What I will say is Lest We Forget Museum of Slavery opened in 2002 and the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center opened in 2004. A little but late to the cause to make such a claim! Or, perhaps the challengers misinterpreted first vs. only?

The Whitney Plantation Mansion

It should be no surprise that the mansion is not the focus here. While you can walk through the lower section, there’s nothing much to see: no staging, no portraits, and no recreation of the lives of the plantation owners’ privilege. Just the bare bones of the mansion, intact and maintained. The Whitney Plantation Mansion is a fine example of Spanish Creole architecture. The house is also one of the few historic American houses with Canova-painted decorative ceilings and wall paintings.

Whitney’s historic outbuildings provide a unique look at the evolution of Louisiana working plantations over time. The Creole mansion and related buildings are a part of the tour and are historically interesting. What I appreciated is that the mansion is not the main attraction. And, I would not consider any of the artifacts on display here attractions. This is a museum, not a tourist attraction.

Slavery at Whitney Plantation

There is a long history of slavery on the Whitney plantation. In 1722, nearly 170 indigenous people were slaves on Louisiana’s plantations. But with time, the number of enslaved increased. Enslaved women worked in the indigo fields growing and maintaining the crop. In most cases, enslaved men worked to produce dye from plants. To create the dye, enslaved workers had to ferment and oxidize the indigo plants. The enslaved people were beaten, killed, undernourished, and overworked. The lives of enslaved people were filled with hard labor. They worked from sunrise to sunset. Rather than caring for their children, enslaved women worked as wet nurses. If you’re unfamiliar with that term, it means they cared for the children of their owners. In layman’s terms, they breastfed their owner’s children.

Whitney Plantation Tour

Whitney Plantation opened its doors to the public for the first time in its 262-year history in 2014. Visitors will gain a unique insight into the lives of enslaved people on a Louisiana sugar plantation through oral histories recorded by the Federal Writers’ Project. Whitney offers people a unique perspective through museum exhibits, memorial artwork, restored buildings, and first-person narratives.

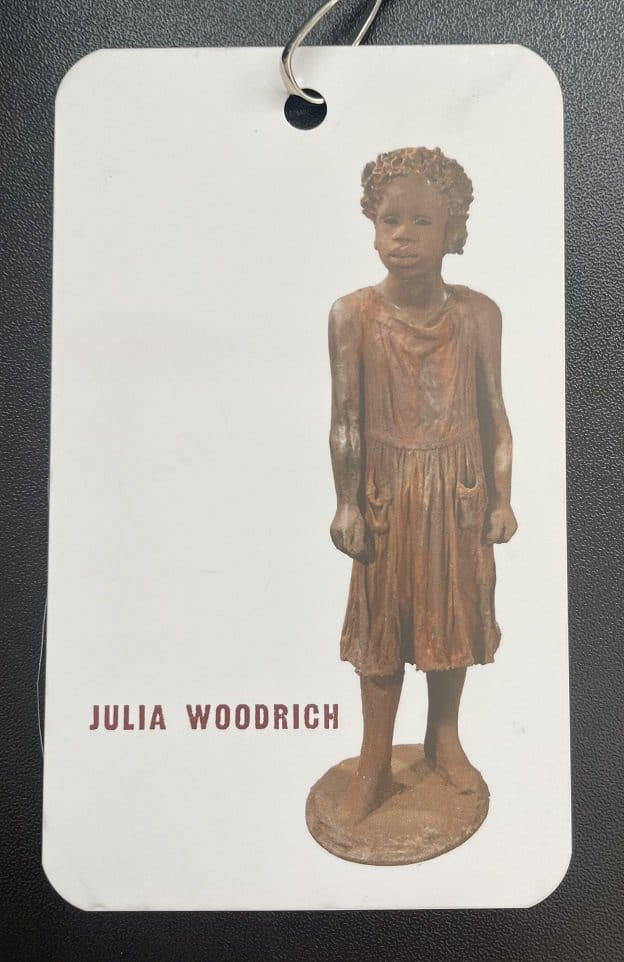

All tours include a memorial to a formerly enslaved person. The memorial card shares each enslaved person’s story, humanizing and honoring their legacy.

Guided Tour

The Whitney Plantation offers guided tours on a first-come, first-served basis. Advanced purchase is highly recommended, as they do sell out. The guided tours are also on a schedule, so even if not sold out, you will probably not be able to join one without a reservation. The guided tour takes 90 minutes.

Self Guided Tour

We took the self-guided tour, and I’m glad we did because we got to take our time. You listen to the history through a headset. Different people narrate each area you visit. It’s incredibly detailed and takes at least an hour to do a tour. If, like us, you listen to all of the additional snippets, prepare to be there for a couple of hours.

The self-guided tour is the only option you can take if you get there, and the guided tours are sold out.

About The Tour

Touring this museum is not for the faint of heart or for anyone that cannot or will not accept a historically accurate account of the plantation era. Nor is this tour for those who want to shrug off this part of American history under the umbrella of “that’s how it was back then.”

I’ve toured a few plantations. They range from completely glamorizing and celebrating southern lifestyles to somewhere in between. Whitney is the opposite. It is 100% focused on slavery and the horrific injustice.

I encourage you to visit if you are genuinely interested in real history. You’ll get a lifetime’s education in a couple of hours. I took this tour with my friend and her daughter, who is in her early 30s. She knew nothing about the slave trade or what life on a plantation was like until this tour. I did not photograph her as she walked sobering through the grounds. I did not need to. I’ll never forget the look on her face; I will never forget the darkness in her eyes or the tears she shed.

The tour is graphic and traumatic, and there are parts where you’d have to be soulless not to shed a tear.

The Slave Quarters

There were 22 slave cabins on the Whitney Plantation before the Civil War and 20 cypress slave cabins that housed field hands. During the late 1970s, they were still in perfect shape when they were torn down and removed from the plantation so that the large tractor-trailers could easily swing into the plantation. According to Steve Barnes, grandson of A.M. Barnes, members of his family advocated bulldozing the buildings on the site to increase the estates’ value. So, the original slave quarters are not on display.

On the site are slave cabins that were acquired from nearby plantations. Notice the large cast iron bowls? These are sugar kettles. During the short harvest season, enslaved people worked around the clock to maintain the massive sugar kettles. Ladling the hot cane juice from one kettle to another. They worked in the dark and often sustained third-degree burns. Infections often result in death. A common occurrence in the crushing mill involved chaining enslaved people together; if they got caught in the wheels, their limbs were amputated on the spot. Add to this; that whipping was a common punishment.

You’ll see sugar kettles all over New Orleans. People use them as fire pits, water features, and planters. There is a high demand for authentic plantation sugar kettles. What in the world is wrong with us? It’s deplorable and ignorant.

One manufacturer I researched makes replicas which is a little more stomachable. I also hope this will encourage some people to avoid glamorizing a genuine historical artifact symbolic of such pain.

Wall of Honor

The Wall of Honor lists more than 350 documented slaves who were enslaved at the Whitney Plantation. There’s a place for each one and their names and quotes narratives of the former slaves.

All enslaved people who lived on the plantation are remembered on a Wall of Honor. On the granite plates, etchings are made, and names are listed non-alphabetically. Using this approach to display the names emphasizes the chaos that accompanied slave life. Its primary purpose is to recognize and honor those individuals whose contributions and work had gone unnoticed and unveiled.

Allées Gwendolyn Midlo Hall

A slave memorial with 107,000 names engraved on it honors those enslaved in Louisiana and is documented in the “The Louisiana Slave Database” built by Gwendolyn Midlo Hall.

Dr. Gwendolyn Midlo Hall

White historian Dr. Gwendolyn Midlo Hall built The Louisiana Slave Database. It contains 107,000 entries documenting the people enslaved in Louisiana from 1719, with the arrival of the first slave ship directly from Africa to 1820. Her work enabled the Wall Of Honor and the Allées Gwendolyn Midlo Hall.

She speaks on the audio tour once you get to the Allées Gwendolyn Midlo Hall. I can’t recall her exact quote on her motivation to document slaves, but it was something like, “I was sick and tired of the lies, and someone needed to share the truth.” Now, I don’t want to evoke debate here. But, for those on the other side of the racial divide in America – some white people care and get it. Dr. Hall is a prime example of an ally, an ambassador, and a proponent of truth, as is John Cummings. Admittedly, each of us can learn from their approach to the world.

Here is a quote from an interview with Afropop Worldwide:

When you were getting started as a historian, what was the state of Louisiana’s historiography? How accurately was the history of Louisiana being told? And what did you feel needed to be done, and how has it changed in the intervening years?

Well, that’s an interesting question. It goes way back. I went to public school here. Historiography then was quite overtly racist. It has improved a bit over time. When I was in public school, the teachers spent about half their time pronouncing racist diatribes, and that was called education. The main theme was that blacks were all stupid, and uneducated, and violent, and dangerous, and that the only way to keep order and preserve the white race was to maintain very severe repression of blacks. So if I could put the history in a nutshell, that was about it. It had to improve from there.

Dr. Gwendolyn Midlo Hall passed on August 29, 2022. As a tribute to his mentor, Dr. Seck designed Allées Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, a granite-block memorial featuring the names of all 107,000 people in her database. According to her request, her ashes will be scattered there later this year.

The Field of Angels

The Field of Angels commemorates the 2,200 Louisiana slave children who died before their 3rd birthday. Some names are listed as “a little slave child.” The museum has a bronze sculpture depicting a black angel holding a baby. There are granite slabs around the statue that list the names of the slave children. It is unknown how many children died on the Witney Plantation, but according to external historical documents, 39 children died here between 1823 and 1863, and only six survived to adulthood.

You will struggle to find a dry eye when you reach this part of the tour. You could cut the air with a knife as it’s complete silence as people read the granite memorials of the little ones. It’s overwhelming and takes some time to take it all in.

Sixty Ceramic Heads

Woodrow Nash produced sixty ceramic heads to commemorate an incident in 1811 when around 125 enslaved people fled the plantation. A total of 95 of these individuals were killed by workers dispatched to round them up. New Orleans’ French Quarter was adorned with spikes bearing the severed heads of some of these escapees.

Stop and think about this for a moment. Seriously?

Some visitors leave negative feedback regarding this display because of perceived horror. But let’s be honest; the truth hurts.

This is another part of the tour where you will not hear a single word. Even though there’s a sign requesting silence, it’s assumed. I observed people reading, and their draws dropped. I could feel their horror as they processed what they read and saw.

The Antioch Baptist Church

Former slaves 1868 founded the Antioch Baptist Church. There were ways in which racism existed during this time in history that most of us have only read about. A burial society was formed at this time by some brave men from the Paulina area. Similarly to our current burial insurance, the society operated as an organization. Members paid nickels and dimes for membership dues, and the society paid their funeral expenses. This society was named Anti-Yoke. Freedom was the meaning of this name – untied and unbound.

Controversy of Plantations

Some displays have sparked controversy because of their association with this shameful part of American history.

People of all races opposed the idea of a slave museum. Some were skeptics, and some were cynics. White people viewed it as a threat to their faith in Southern heritage, American culture, and glory. Some have condemned the museum for inspiring unwholesome pity for black people. Many argued that a slavery museum built by a white man who owned a plantation was another example of continued profiteering off the suffering of black people. According to some black people, their ancestors built their wealth with blood, sweat, and tears; now, the descendants seek to make money by selling their version of the story.

Fortunately, Whitney Plantation does not profit on the back of slavery. The Whitney Institute (DBA Whitney Plantation) is a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization dedicated to educating the public about the history of slavery and its legacies.

FAQs

What You Need To Know

- It’s scorching hot! Even though there are misting stations to cool off under, it’s blazing hot. Wear a hat or bring an umbrella shade. Lastly, don’t forget water!

- There are gators on the property! We saw them with our own eyes. I am sure the museum relocates them as they mature, but they are there. So keep an eye out.

- While I encourage you to take your children, there are some graphic elements you should prepare children for.

Bonus: Scenes from “Django Unchained,” starring Jamie Foxx, were filmed at the site.

Closing Thoughts

Whitney Plantation is one of the country’s first slavery museums. It has been mentioned by numerous publishers and socialists worldwide due to its historical and societal significance, and it welcomes hundreds of thousands of guests annually.

The museum pays tribute to more than just the enslaved people who worked on its sugarcane farm. Cummings collected relics and brought buildings that weren’t originally on the property. For example, the slave cabins and the shocking slave cage used to transport and sell enslaved people.

I was so impressed with the museum. It’s one of the most educational tours I’ve taken in a long time and worthy of anyone’s time. Whitney’s approach is a model that all plantations should follow. Nottoway, in particular, stands to learn a lot.

I hope this is the first of many pieces of history set right. Most importantly, I hope everyone reading this will consider visiting to broaden their understanding of America’s past.

Looking for more historical posts? Start here:

- Dachau Concentration Camp – Why You Should Visit

- Nottoway Plantation – The Most Controversial Plantation in Louisiana

- Inside Magnolia Plantation – South Carolina

- Solomon’s Castle Ona, Florida

- The Howey Mansion – Howey-in-the-Hills, Florida

- The Marquee New Orleans – Bluegreen’s Augmented Reality and Interactive Art Resort

- The Wonder House – Bartow Florida

We participate in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Brit On The Move™ Travel Resources

Ready to book your next trip? Use these resources that work:

Was the flight canceled or delayed? Find out if you are eligible for compensation with AirHelp.

- Book your Hotel: Find the best prices; use Booking.com

- Find Apartment Rentals: You will find the best prices on apartment rentals with Booking.com’s Apartment Finder.

- Travel Insurance: Don’t leave home without it. View our suggestions to help you decide which travel insurance is for you: Travel Insurance Guide.

- Want to earn tons of points and make your next trip accessible? Check out our recommendations for Travel Credit Cards.

- Want To Take A Volunteer Vacation or a Working Holiday? Check out the complete guide to how here!

- Want to Shop For Travel Accessories? Check out our Travel Shop.

Need more help planning your trip? Visit our Resources Page, which highlights the great companies we use for traveling.